Lobbying for London: Devolution and Governance Reform with Antonia Jennings, CEO of Centre for London

London is one of the wealthiest, most visited and most significant cities in the world. It is the home of arguably the world’s financial capital, and was once the beating heart of an empire that spanned a quarter of the globe. It is also a cultural and educational powerhouse, hosting several top 100 global universities and many world-class sports clubs, stadiums, arenas and events.

But despite all this, London in many ways is a city that is creaking under its own weight – socially, politically and economically. Often perceived as being punished for its success, and simultaneously perceived as succeeding because of favouritism towards it, it is a city of many contradictions, including some of the richest and poorest people in Europe, towering skyscrapers as well as perhaps the oldest houses in the world, excellent public transport yet awful cycle routes, pioneering but confusing governance, and the jewel in the crown of the UK but significantly lacking in meaningful autonomy.

And ironically, or perhaps in true London fashion, the woman in charge of advocating for how we should sort it all out is Antonia Jennings, of Liverpolish descent by way of Wales, but by now a proper Londoner.

I met with Antonia a few months ago to discuss her upbringing in Cardiff, her rapid ascent up the think tank world in London to become a very young CEO, and her thoughts on the state of the capital today.

OB: What’s your backstory?

AJ: My mum moved to the UK from Poland when she was about 25/26, before Poland was in the EU, so it was harder to move at that time, and she came with quite limited English. She ended up meeting my English dad and then they had me. They then split up and I stayed with my mum. My dad stayed in London and was very much in my life until he died in 2020. When I was about four or five, my mum got a job in Bristol. She was a single mum at the time and we didn't have much money, so whilst that felt like quite a dramatic move, living in Bristol was cheaper and it was a good job, so it made sense. We stayed there until I was nine and then and my mum met my future stepdad. He was a lecturer at Cardiff University, so we ended up moving with him to Cardiff. When we moved, I started going to Coryton Primary School for the last couple of years of primary school and then went to Bishop of Llandaff for secondary school, which I really enjoyed. It was a great experience.

OB: So how did you decide what to do next?

AJ: Both my mum and dad were quite adventurous people – my mum had moved from Poland and we'd moved around a lot and in quite a typical second-generation immigrant way, my mum put a lot of pressure on me to do well but also gave me sense of, “You can do anything and be anywhere.” And I think both those things meant that, once I left school, I was always going to go somewhere outside of Cardiff for university. Staying put didn’t really feel like an option. The guidance from my mum felt more like, “Spread your wings and go wherever you want.” I ended up going to Manchester Uni for my undergraduate degree and had a really good time. Then I took a year out and went to South America for a year with my then-boyfriend and following that we both moved to London to do our masters. I went to the LSE and graduated in 2015. So, unbelievably, this is pretty much exactly my 10-year anniversary of being in London.

OB: Congratulations!

AJ: Thank you! My master’s had been in Politics and Communication, which was essentially about the study of public opinion. Where does it come from? What influences it? How can we change it? And it's all about the relationship between the state, the media and people, basically. That’s still very much an area of interest. When I graduated, I wasn't sure exactly what I wanted to do, but I knew wanted to do something related social justice, something about making people's lives better. But I didn't really have a clearer idea than that. So when I finished my master’s, I was just googling any social-justice-related terms and looking for work. I just wanted to get a job somewhere doing something good. I ended up initially getting an internship in a big international climate NGO, then following that I moved into the domestic policy think tank sector, largely focused on economic policy. I'd studied economics at university and I spent effectively about seven years working on national progressive policy of all sorts of descriptions. But my entire career up to that point had been under a right-wing government, and given that I’m progressive politically, I became increasingly frustrated with the fact that working on national-level issues meant that, often, the biggest win that you could really get was a minor amendment to otherwise quite regressive policy. So, to me, the scope for impact was limited under the national government. To that end, about five years ago, I made quite a conscious decision to move into working on local economies and local economic development and on sub-national policy more generally. I got a job working at an organisation called CLES [the Centre for Local Economic Strategies], based in Manchester, and through that I worked with councils, combined authorities and the devolved administrations in Wales and Scotland. I’d been employed as CLES’s first London-based member of staff, so my job on paper was in part to build up the organisation’s presence there. But I started working there at the beginning of COVID, so that meant that I couldn’t get very far in achieving that goal by networking and building up a bigger physical presence in London. Inevitably, I ended up getting pulled into other non-London projects because they were in need of additional capacity.

OB: Did you at least have an impressive title?

AJ: Well, I was “Associate Director”, so I suppose so!

OB: It sounds like you could have been 60! So what happened afterwards?

AJ: I’d been in the role for nearly three years, and I’ve always been quite ambitious, so towards the end of my time there I started to think about what was next, and I’d felt increasingly that I wanted a physical team around me. However, I was happy at CLES and I decided that I would only apply for something if I really, really wanted it. So that meant that I basically started applying for things that I thought I wouldn’t get! During my time at CLES, I’d spoken at a few Centre for London events, and I was approached by the outgoing Chief Exec about whether I wanted to apply for his role. It was quite terrifying because it was a big jump in responsibility. I was 31 at the time, whereas my predecessors had been men in their 50s or older. But I ended up getting it, which was very exciting. So the board made quite a bold choice to appoint me. I think the decision was made in part because the board is comprised of people that have been involved with London’s major institutions, like TfL, the GLA, the housing associations et cetera, and I think they appointed me as a bit of a change in direction, a new approach for thought leadership in a city which despite a lot of best intentions, has been struggling and stagnating in a number of ways. London is also a young city, and I think the board felt it was right to reflect this in the charity’s leadership. They were aware that I’d need some investment in my development in order to be able to lead the organisation, because I was a first-time CEO, but also because a lot of central London-specific issues were quite new to me, and thankfully the board has provided this.

OB: Was there any hesitation about accepting the role when you were offered it or was it just too good of an opportunity to turn down?

AJ: No, not at all. Like I say, it was a big jump and that was quite nerve-racking, but as you say, the opportunity was too good to turn down and I was looking for a challenge and it fit pretty much exactly within the type of work I was looking to do.

OB: How long has the Centre for London been running? Is it quite an established institution?

AJ: We've been around since 2011, so about 14 years now. So not new but not necessarily an “institution” yet.

OB: Was it set-up in response to the Coalition Government and austerity? Or was the timing coincidental?

AJ: No, it wasn’t that. It was spun-out of the think tank Demos. It was justified as its own organisation because, despite this perception that London is the land of milk and honey, actually, in terms of metrics of deprivation, London has some of the worst outcomes in the country. In terms of a lot of poverty metrics, extreme need is found across the UK, but there is a specific manner in which it manifest in London. Housing costs, for example, are the biggest drag on poverty in London, jumping our poverty levels from 15% to 25%. In terms of inequality, to give another example, it's London that is the most unequal region. This has effects across our public services, housing market and opportunities available to Londoners. London is not the finished article in terms of development. Secondly, it has a very unique operating environment, which means that a lot of the policy recommendations that come out of national think tanks can't necessarily be translated into a London context simply because of the scale of it and because of its unique structure, for example even the GLA is unique as a governance form in this country. And then thirdly, for a long time, there's been an anti-London bias that comes out of Westminster. All of which led the founder of Centre for London, Ben Rogers, to conclude that there needed to be a place-based think tank dedicated to London – an organisation that could answer London's need for independent thought, leadership and policy development.

OB: Which is funny because I think anyone outside of London would say the government's always prioritising London over everywhere else – every transport project is in London, every major company is in London et cetera. So it's interesting that there is obviously this differing perspective. But I think you're right. London on the surface obviously looks big and shiny and rich, but clearly it's got very deep, systemic issues that are belied by its aggregate metrics on productivity and wealth etc.

AJ: Precisely, and it's a funny one because it's a bit of a contradictory city in the sense that, if you are a poor kid in London, you're more likely to breathe toxic air, you're more likely to experience crime of different descriptions. There's a whole variety of ways in which you are more likely to suffer, with the exception of educational outcomes. London consistently leads the nation in terms of GCSE and A-Level outcomes. If you're a young, poor kid in London, you are more likely to be offered opportunities than if you're a young, poor kid in the in the Northeast. And I think that that skews people's perceptions a bit of London. But that is very much a function of any capital city. It’s similar in Paris and in New York.

OB: How do you as an organisation decide what your priorities are? I know you work on specific projects where you work with sponsors and funders on subjects agreed with them, but presumably you have your own broader priorities that you work on, so how do you decide those? Do you do surveys of Londoners and ask what matters to them, and base it on that, or do you have your own analysis of what the challenges are that London faces?

AJ: All of the above. I essentially inherited an organisation that lived on a project-to-project, hand to mouth basis, and I would suggest there was a bit of an absence of a coherent overall agenda, a product of the pandemic among other things. There was a lack of a sense of vision as to what we were trying to create. So after a few months of getting my feet under the desk, we spent all of last year consulting on a new strategy and that involved, as you say, surveying Londoners, which we actually do every quarter with a representative sample of Londoners to find out what their concerns are, their appetite for different solutions and a whole range of other things. Obviously, it also involves speaking to our stakeholders, our funders and people that we’re trying to influence. That consultation is more focused on where people think Centre for London has best added value in the past, what the underexplored areas might be, because, for example, there are a lot of ten-point plans to fix London's housing crisis out there, so how can we add something different? We also wanted to ask people how we should best package our work. I feel quite strongly that think tanks sometimes imprison their best ideas in 70-page reports, publish them and then forget all about them. But that doesn't create a better world. So there was a lot of discussion around whether we could do more interesting convening work and building-up unusual coalitions and not just produce research. And on top of the consultative work, we did an assessment of London’s current situation and of the current political moment. So, for example, we obviously had a General Election last year, which meant that, for the first time in a long time, leadership in both London and nationally were aligned, so we wanted to explore what opportunities that might create. London also has a target net-zero date of 2030, so we also had to incorporate that as a major timely priority, including what was still left to do. So all of that's come together in a new strategy that came out at the end of last year, which hopefully offers a coherent vision and framework to guide our work and allow us to work more programmatically on a multi-year basis. The new strategy has three connected pillars of developing, decarbonising and governing London, and in the first instance each of those pillars has a two-year work programme attached to them, which we’re currently delivering.

OB: What’s CfL’s position on devolution and governance? What more should be done in that regard to support London in achieving better outcomes?

AJ: I would suggest that London’s governance arrangements need quite a lot of work. London was the first region with a devolved arrangement in England, so in that sense it was the pioneer and the guinea pig to see how devolved governance would work. But, what we’ve seen in the 25 years since the GLA was established is devolution accelerate across the rest of the country and now in in some areas, other regions are more devolved than London, which is a tricky situation for a capital city to be in. And even under this government, the Labour government has released an English Devolution White Paper that indicates that we're soon going to be in a position where other regions are going to further outflank London in terms of the powers they have, including, crucially, revenue-raising. And from my perspective that's a big shame because devolution should be a cross-party political priority. There is a lot of even economically orthodox evidence from that right that shows that greater devolution and local autonomy is correlated with higher growth, higher productivity and more trust in politics - all the things that we want London to have.

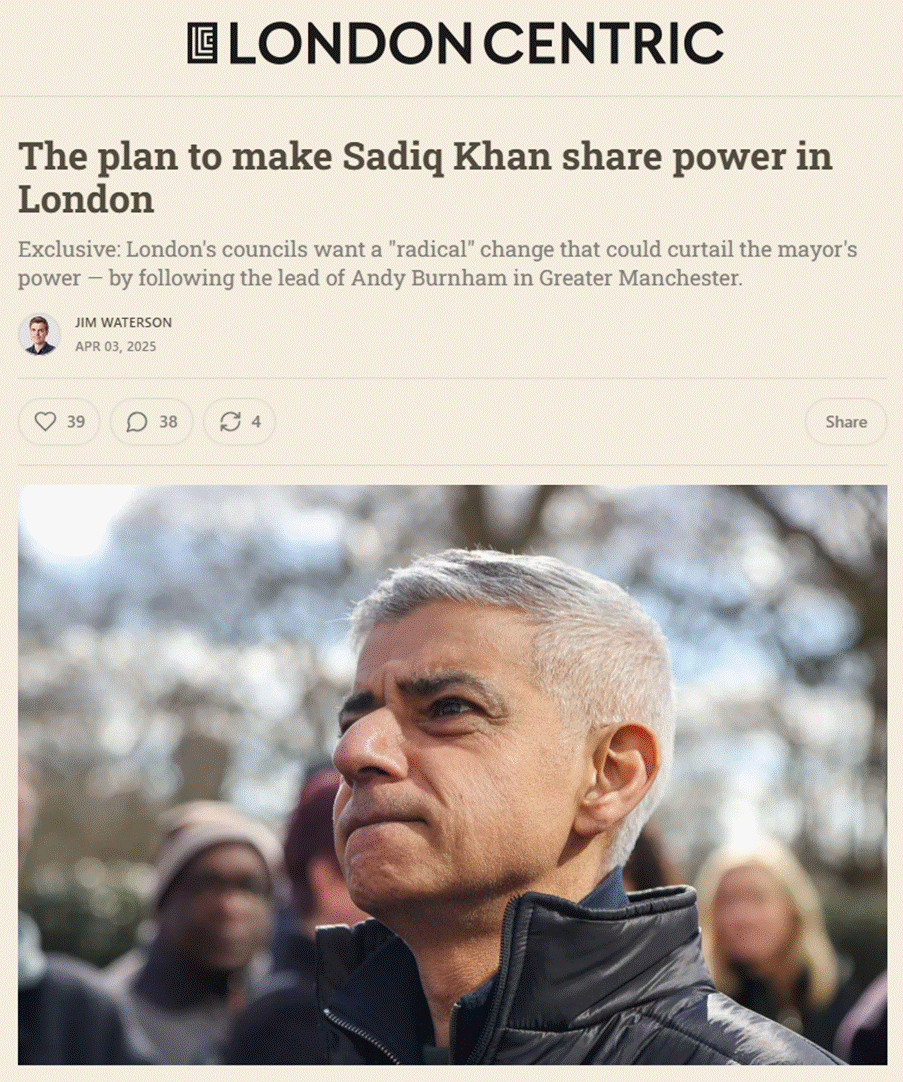

OB: That brings me very neatly to my next question; why do you think government has historically been so reluctant to devolve governance and fiscal powers to London, and to even give it an integrated settlement? I know you said there’s an anti-London bias in Whitehall, but it must be more than that, surely? Like you say, presumably the government wants London to succeed, so it's odd that it hasn't. And secondly, what do you make of the London Councils proposal to the Mayor for greater power-sharing? From my understanding, they want to copy the model of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, and there’s some questions about whether that would actually be more effective than the current model. It’d be great to get your thoughts on that.

AJ: It is quite difficult to explain the anti-London bias beyond there being a sense that London has gotten more than its fair share historically, and the financialisaton of the capital has come at the expense of other UK regions. But just look at the Spending Review from earlier this year. The Chancellor named and shamed London as an area that, by her implication, had gotten too much. She had a line in there saying that “past governments have underinvested in towns and cities outside London and the South East”, suggesting that London has had it too good, which is really disappointing. I mean, even in the Levelling-Up days, it was always strongly implied the priority wasn’t London. And now we're in the position where the Chancellor has explicitly said “Not London.” So I think there's a long-held Westminster belief that policy needs to appeal to certain types of constituents that either don’t like or do not live in London, or some combination of both.

I would also suggest, and I hope that some of our stakeholders don't get annoyed, but I think it would be difficult to disagree with this; London doesn't have one voice when it makes the case for what it wants. This is partly a product of the scale of having ‘one ask’ for the city. So, as you mentioned, we have the GLA and London Councils. They're the two biggest political organisations in the city and they have publicly different ideas about how London’s governance needs to change. On London Councils’ proposal, there are serious issues with the current setup and there are democratic challenges.

As for the merits of the proposal, it's worth noting that when London Councils made that intervention and called for shared decision-making, something that got lost is the fact that they weren't saying they wanted shared decision-making on all aspects on the Mayor’s role. In fact, on much of the pan-London remit of the Mayor, like big transport projects or policing et cetera, they haven’t said they are recommending shared decision-making, and indeed appreciate the pan-London look these issues necessitate. Because these are less borough-by-borough issues. So they were only really pushing for shared decision-making on issues that play out quite differently depending on the borough.

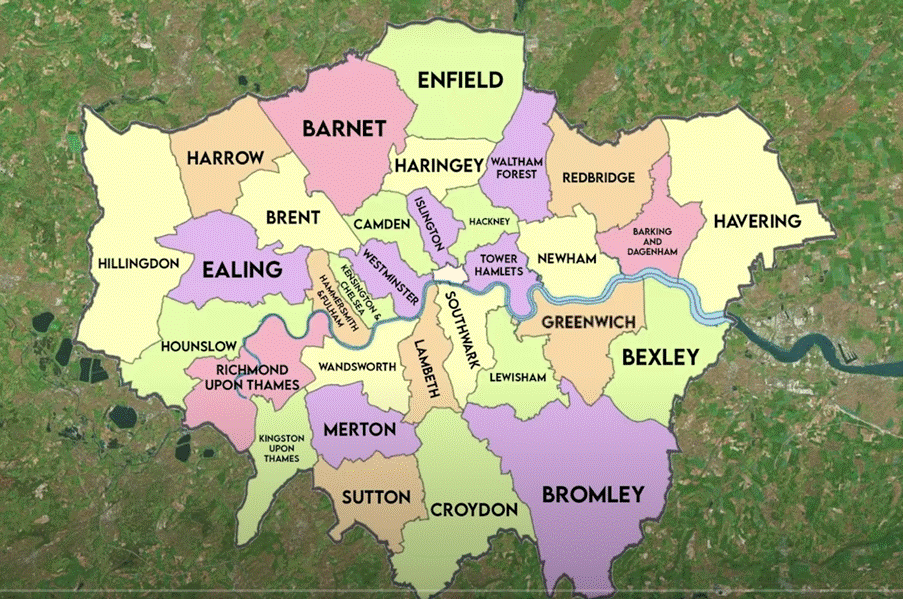

I would welcome more shared decision-making on some aspects of the Mayor’s remit. It's worth emphasising the scale of London compared to other regions. Obviously it's the biggest city in the country, between nine and eleven million people, depending on where you draw the boundary. But just to put it in some context, the Borough of Hounslow, which to a lot of Londoners in the city will just be some borough in West London, has an economy that's bigger than the nation of Iceland, so that just shows you the scale of what we're talking about. I would suggest that there is, if anything, more of a case for a council perspective in a pan-city debate than in any other part of the country, including in established combined authorities such as Greater Manchester.

OB: Obviously CfL is an independent organisation. Do you view the remit of the organisation as being as much about scrutiny as it is about offering solutions? You obviously have a ringing endorsement on your website from Sadiq Khan and he says you do great work. Is that a problem that he thinks you do fantastic work? Or is that a good thing?

AJ: If you're a regional think tank, of which there are very few, actually - most think tanks are thematic - having the most senior politician of your region back your work is definitely a good thing. They’re probably your single most important stakeholder, or at least their institution is, so I don't think it's a problem. We have endorsements from across the political spectrum and also from central government down to community groups, so I think having that ecosystem of endorsements is very important. But I would stress that we say a lot of things that the Mayor doesn't agree with as well, and that's really our function in the city - to act as an outrider to institutions around the art of the possible, thinking outside of political cycles and thinking outside political constraints as well. There’re also things that the Mayor or local authorities might be interested in knowing about that local area or about the future, but for various reasons they can't commission research into it in-house. It could be because it stretches outside of the political calendar or term lengths or because the local authority simply doesn’t have the capacity or the skills to undertake this work. Local government is in the wake of a decade of brutal austerity that means they’re drowning under temporary accommodation pressures or indeed, adult social care costs or whatever it might be, which are more immediate and urgent concerns, so often external support is needed to carry out the kind of work that we do.

OB: Housing is obviously an increasingly salient issue in the UK, but nowhere more so than in London, and lots of think tanks have been making proposals for how to increase the stock of housing. What are your thoughts on what needs to be done? Do you think we need to upzone existing urban areas and increase the density, or do we need to build new towns in London as some have proposed? What do you think is the most persuasive vision?

AJ: Housing is an extremely tricky issue because every plausible route forward from this point involves big winners and losers. If you think about the many Londoners who do own their home, who tend to be older, often that home, that asset, is their sole source of retirement or care costs when they get older and/or retire. So whilst we instinctively want to bring down affordability, we create another problem potentially in the state then having to pick up care costs for old Londoners, which is not cheap. A long-term supply uplift is definitely needed. And whether it's suburban new towns or more density in the middle, I think we need both. But what’s crucial to note is that, even with a large house-building drive like Labour want to pursue, that’s going to take years to kick in and much longer than that to have any discernible impact on the cost of housing, because any additional housebuilding is barely going to touch the sides of the total existing stock and the unmet demand. So we also need to do something for homeowners and renters today who are living in low-quality housing and who have unaffordable rents or mortgages, because those issues are not going to be solved any time soon by housebuilding alone.

OB: Antonia Jennings, thank you very much.